First of all, I want to celebrate today’s edition with each one of you who subscribed to this newsletter! I’m beyond happy that we are already over 100 people here. You inspire me to continue writing and I’m genuinely curious where this writing & tennis journey will lead me. Thank you!

I’ve tried to sit down and write this newsletter several times over the past few weeks, but each time, I ended up closing the document, frustrated and blocked, like I was hitting a wall. I put so much pressure on myself to stick to a bi-monthly schedule that I lost the simple joy of sitting at my desk and letting ideas flow freely - the way something like this naturally came to life.

I know there’s no such thing as a real "writer’s block," but I’ve realized the creative process is meant to feel like the right mix of discomfort, pleasure, inspiration, and just enough pressure to move forward. Lately, though, each time I opened this document, all I felt was judgment, pressure, disappointment, and self-criticism. (It probably sounds familiar to many of you.)

Aaand that’s how today’s theme came out, instead of writing about my love for Carlos Alcaraz (we’ll keep that for a next edition, I promise).

One of the reasons why I love tennis so much is that it’s the best metaphor for life. In both tennis and writing, the greatest barrier is rarely a lack of skill (that can be practiced, learned, unlearned, relearned) – but rather the mind’s tendency to interfere in the process.

In ‘The Inner Game of Tennis’, a timeless guide on the philosophy of tennis and life written in the 1970s, Timothy Gallwey emphasized the idea that human beings don’t have a single mind, but two. A conscious one and an unconscious one, “with both systems underpinned by different neural circuitry, and the interaction between these two different systems might hold the key not just to success in sport but to much else in life besides.”

He calls the conscious self ‘Self 1’ and the unconscious, automatic self ‘Self 2’ and he starts the book with the assumption that the way Self 1 talks to Self 2 might hold the key to sporting success and failure.

Imagine, for a moment, these two selves as two different people who show up whenever we try to do something. If we were to observe them over the course of a day, what would we notice about their relationship? Would it look healthy and constructive? Would they work together as a team?

Or would we see one constantly criticizing, pressuring, and judging the other, telling them they're not enough, that they should move better, hit better, write better — as if the second person were stupid or forgetful?

The sad or happy truth is that Self 2 (the unconscious individual) is anything but stupid. He hears everything, never forgets anything, and is always awake, as Timothy explains in the book.

The real problem in this relationship isn’t that one self gives instructions and the other executes; it’s that the first also insists on being the evaluator. Gallwey points out that there’s a subtle but powerful mechanism at play: while positive feedback can feel so rewarding, it inevitably sharpens the blade of self-criticism. If success earns praise, setbacks must earn blame.

Over time, this internal evaluator becomes automatic — not because others continue criticizing us, but because our nervous system has learned to anticipate judgment. Even when no coach, no editor, no opponent is present, the mind keeps up the running commentary. This is how self-sabotage begins: we internalize external voices so completely that we don't need them anymore. Our own neural wiring takes over the job of surveillance, correction, and protection, believing it is keeping us safe from failure, when in fact it’s creating the very fear and paralysis we seek to avoid.

Since I started watching tennis, I’ve always wondered: how is it that some players can turn a match around from the brink of defeat, while others, standing on the edge of victory with match point, collapse with a single mistake?

How can a moment change everything? And how is it possible that some athletes, the greatest the sport has ever seen, managed not just to dominate, but to stay at the top for nearly two decades? Yes, you heard me right — twenty years of Rafa Nadal, Roger Federer, and Novak Djokovic (who, remarkably, is still competing at the highest level), showing up day after day in a sport where, for most players, losing is far more common than winning. They were the exception. They were the ones for whom tennis meant winning more than losing. What did they discover that others didn’t?

Playing a sport at the highest level, the difference between a top 10 tennis player and the rest is rarely technical. Everyone in the top 100 can hit a forehand, a serve, a backhand with world-class precision. One of the things I discovered that separates the greats is their ability to manage the mind under pressure – to stay clear when matches are decided by a few points, to recover emotionally after mistakes, and to keep competing even when the body or spirit breaks.

There are players like Alexander Zverev, who reached three Grand Slam finals and lost each of them – this year’s Australian Open final, you could see that it was his mental side that didn’t work out. There’s also Andrey Rublev, one of the most emotional players on tour, who often turns frustration inward, sometimes hitting himself with his racquet or punching his legs. Rublev’s problem is rarely about technique — his groundstrokes are some of the heaviest on the circuit — but about his difficulty in self-regulating. And there’s Nick Kyrgios, a player of rare talent and touch, whose resistance to discipline and structure, and whose battle with depression and self-destructive habits, turned talent into an unpredictable firework show.

Take, on the other side, Nadal. The figure of self-discipline, humility and controlled intensity. Since he was 19 years old, he played with a rare and chronic foot condition known as Müller-Weiss syndrome and he often had to take painkillers before matches to manage the pain in his foot. He even wears custom-made shoes, built to accommodate the different sizes of his feet and to protect his fragile bone structure. After he won his 14th French Open title in 2022, he declared that his foot was completely numbed during the match: “I was playing with no feeling in my foot, with a nerve injection. That's why I was able to play." It brings to mind a phrase from David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest that seems to describe Nadal’s warrior spirit:

“Everything I’ve ever let go of has claw marks on it.”

There’s no comparison between these players. Even being in the top 1000 is an extraordinary achievement in a sport where thousands try and few break through.

But especially within the top 10 or top 20, it becomes clear: some players possess a set of internal tools — psychological, emotional, physical — that others are still searching for.

And yet, even here, mental resilience and hard work are not the whole story. As David Epstein shows in The Sports Gene, genetics plays a crucial role. Some players are born with physiological advantages — lung capacity, fast-twitch muscle fibers, joint flexibility — that no amount of practice can create from scratch. "Differences in innate capacity constrain the heights of performance," Epstein writes, "and no amount of practice will make up for inherent biological ceilings."

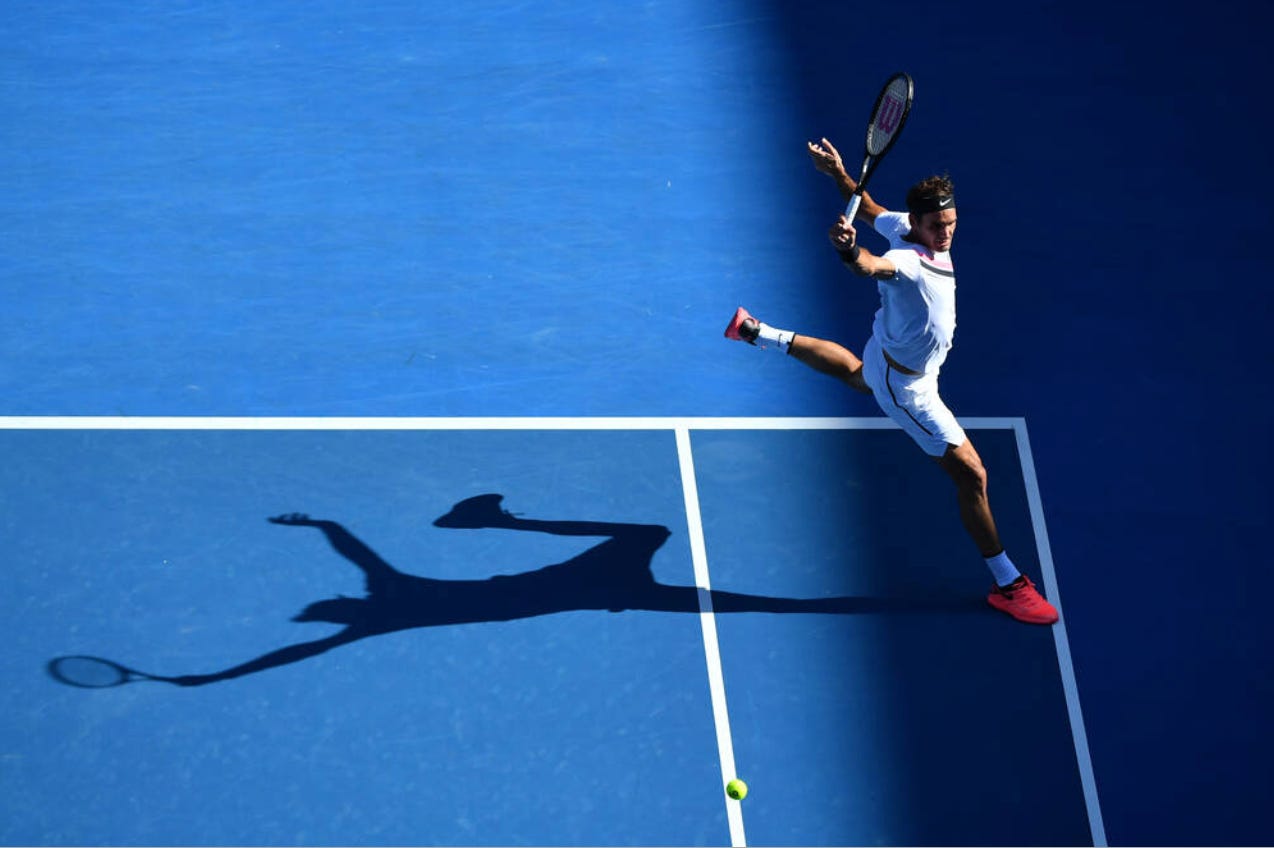

Training is essential, but it cannot fully overcome certain physical limitations. The greatest athletes are both born and made. Roger Federer is a striking example. Beyond the elegance of his game, Federer’s body gave him tools few others had: an extraordinary kinesthetic sense – the ability to feel and control his body's movements with effortless precision. Exceptional hand-eye coordination, and a body that, for most of his career, resisted the kinds of injuries that affected so many of his rivals. His movement looked light, almost like levitating at times, but beneath it was a neuromuscular system operating at a level few athletes could replicate, no matter how hard they trained.

There are, without a doubt, a few rare individuals that were born and made almost divinely for greatness – prodigies whose talent appears innate like Federer, Nadal, Simone Biles, Tiger Woods, Michael Phelps and many exceptional others.

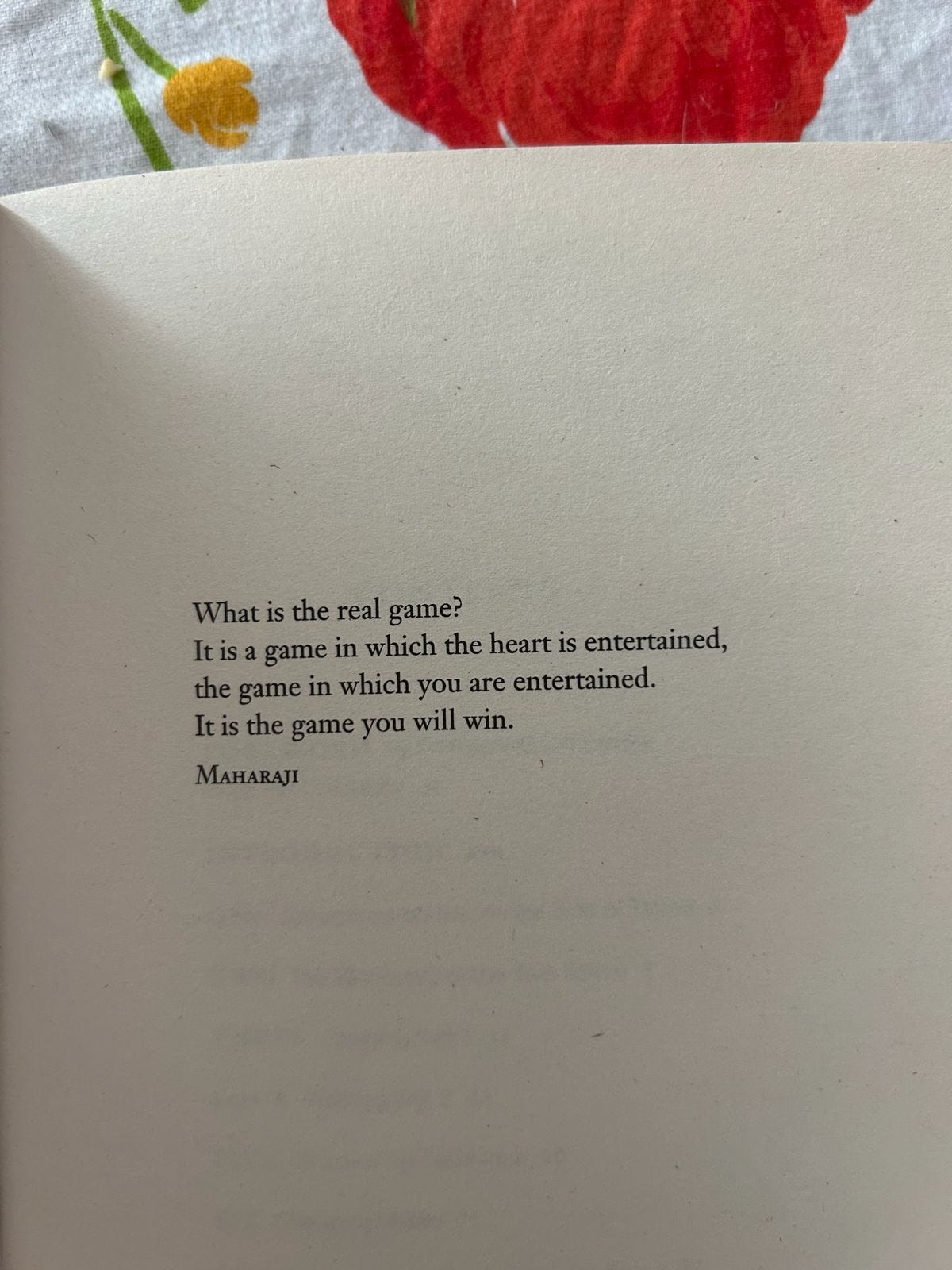

But for the rest of us, either we are talking about tennis, writing or another pursuit, true mastery lies elsewhere. It lies in giving ourselves permission to let go, to lock that Self 1 in another room and let Self 2 write freely, loosen that arm and let the shot flow, stay curious, put that pen to paper spontaneously and resist the urge to evaluate the moment. Our true mastery lies in “letting ourselves gain the experience of peace in a moment when the mind is relatively still, it’s about seeing the ball differently and listening to it, it’s about being aware of your breathing and what it is to be in the moment.”

See you soon, and may you let it happen, whatever that is.

Theodora